“Hermes wants for nothing for through hard work, cleverness, the weaving of fine tales and simple treachery or theft he can get whatever it is he wants and even managed to sneak his way into the bed of the lovely Aphrodite whose soft, warm flesh delighted him so. Hail Hermes, is there anything you cannot accomplish? If so I am ignorant of it.”

Sannion, Praise for Hermes

“A son, of many shifts, blandly cunning, a robber, a cattle driver, a bringer of dreams, a watcher by night, a thief at the gates, one who was soon to show forth wonderful deeds among the deathless gods” (Homeric Hymn 4, trans. Evelyn-White). This is the child born to Zeus and the Pleiades nymph Maia after they joined deep in her cavern, where she avoided the company of the immortals. The herald of the gods was born at dawn on the fourth day following Noumenia, and by nightfall had invented sandals and the lyre and stolen Apollo’s herd.

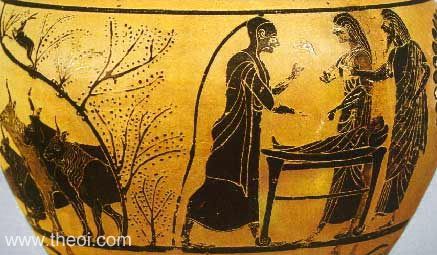

Hermes’ most infamous trick recorded him for posterity as a god of cunning and thievery. He leapt from his cradle craving meat, and only the cattle of another god was good enough for the newborn. When he came across the cows of far-shooting Apollo, he fashioned them shoes just as he fashioned himself the first pair of sandals to protect his soft, delicate little baby’s feet, leading them trackless to a grotto as “divine night, his dark ally,” draped over the world (Homeric Hymn 4).

Even as an infant, Hermes observed the eyes of the guard dogs and local shepherds following him as he led Apollo’s cattle out of the fields. The hounds he vexed and made forget about their curved-horned charges, and the old man tending his nearby flowering vineyard he offered incentive for his silence: “Old man, digging about your vines with bowed shoulders, surely you shall have much wine when all these bear fruit, if you obey me and strictly remember not to have seen what you have seen, and not to have heard what you have heard, and to keep silent when nothing of your own is harmed” (Homeric Hymn 87). The man, called Battus (“chatterbox”) by the locals, eagerly agreed, announcing with his finger pointed at a nearby rock, “Proceed! You’re safe; that stone shall tell sooner than I!” (Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. Melville)

Still skeptical of the old man’s word and faith, Hermes of many shifts changed his guise and approached the tiller again. “Have you seen someone leading a herd of cattle from this meadow? Speak up, they’re stolen; when recovered I will give you both a bull and sow from my missing stock.” The elderly man spoke up quickly, pointing to the hill where they could be found.

Zeus’ son laughed in bitter amusement. “So you betray me to myself, I say!” For his treachery, the Winged One turned the tiller into the telltale stone, plagued forever by heat or frost.

Following this betrayal and Hermes’ first expression of wrath, he led the cattle the rest of the way from the hill to the cavern. There he removed two from the herd, sacrificing them in honor of the gods; he ate conservatively of their meat, burning the rest in offering, and let their hides dry upon the rocks. As he emerged from the cave, a tortoise slowly crossed his path; praising it as a blessing from the gods and a charm against witchcraft, he killed it and hollowed out its shell, and between it and the remnants of the two cows, he fashioned a lyre.

Though a guardian of darkness and death who travels best in the shadows, it was still he who told his mother, upon slipping back into his swathings and crib and being scolded for his shameless thievery, that it is better to live within society than to hide from it, even as a rogue:

“I will try whatever plan is best, and so feed myself and you continually. We will not be content to remain here, as you bid, alone of all the gods unfee’d with offerings and prayers. Better to live in fellowship with the deathless gods continually, rich, wealthy, and enjoying stories of grain, than to sit always in a gloomy cave: and, as regards honour, I too will enter upon the rite that Apollo has. If my father will not give it to me, I will seek–and I am able–to be a prince of robbers.”

Homeric Hymn 4, trans H.G. Evelyn-White

When Leto’s golden son found his herd missing, he consulted the locals, but the lack of tracks left them bewildered. His investigations were more fruitful when he looked to the sky flying high above was a long-winged bird, a sight that immediately informed him that it was the youngest son of Zeus who was to blame for his loss.

As the newborn Moon rose to take her place in the night sky, Apollo rushed to Maia’s cavern to confront the crafty child who had hunkered down in his sweet-smelling blankets. In his rising anger, the bright god threw open all the cabinets and cupboards, though all he found within them were gold and silver, the nymph’s ethereal gowns, nectar, and ambrosia; his cattle remained hidden.

“Come now, child, tell me of my cattle, or we shall soon fall out like enemies. I will cast you down to Tartarus, and though you may be the son of the King of the Gods and this beautiful mountain-nymph, neither your father nor your mother shall free you or bring you back into the light; the gods will leave you trapped beneath the earth, king among cursed and fallen men.”

From his place snuggled deeply into his cradle, his lyre tucked beneath his arm, the infant Hermes told Apollo with cool nonchalance, “Why the harsh words, Apollo? What sort of way is this to introduce yourself to a newborn? And what are these ‘cattle’ of which you speak? No one has told me of these creatures, and look at my infant body and soft feet, the world out there would destroy me! And anyway, I wish not to be a shepherd; the only things that interest me are breastmilk, blankets, and baths like any babe–remember that I was only born yesterday. But if you’ve so convinced yourself of these things in your frenzy, I’ll swear an oath on the head of my father that I am not guilty of stealing your cows, nor have I seen the one who is–whatever these ‘cows’ may be.”

Apollo threw back his head and let out his soft laughter. “Oh, you rogue, crafty, cunning deceiver, you speak so innocently and eloquently that I surely believe you have broken into many a well-built house this night and left more than one poor wretch without even his last chair.”

Hermes’ eyes darted back and forth, brows arched and lips whistling with feigned innocence, and Apollo continued: “It is not the last time you will steal a herdsman’s livestock when you crave a meal, I’m sure. But for now, night’s comrade, rise from your cradle; let’s meet those gods who will surely call you the prince of robbers after this.”

At this, Apollo lifted the boy from his nest and carried him on the long trek to Mount Olympus, all the way with the one doing his best to deceive the other; but Apollo is a god of many shifts, as well, and saw right through Hermes’ attempts. When the young god finally recognized this, he shrugged and consented to walk before Apollo as they approached their father, interrupting an assembly of immortals gathered at dawn’s eruption of light. As they arrived before Zeus’ throne, his thundering voice inquired of the God of the Silver Bow just what he meant by bringing this herald-god before the council.

“Father, you think me fond of spoil, but just wait until you hear the tale of this young god’s robbery–though I am awed by his skill; I have never encountered such a cunning thief. He stole away my cattle from the meadow where they graze and left behind only the most marvelous tracks, as if they had all walked away on slender oak trees. He lied through his teeth, invisible in his cradle, though all the tells of deception were there.”

As Phoebus took a seat, young Hermes approached Zeus their father, pointing straight at the great god as he remained true to the tale he had spun for Apollo:

“Zeus, my father, indeed I will speak truth to you; for I am truthful and I cannot tell a lie. He came to our house to-day looking for his shambling cows, as the sun was newly rising. He brought no witnesses with him nor any of the blessed gods who had seen the theft, but with great violence ordered me to confess, threatening much to throw me into wide Tartarus. For he has the rich bloom of glorious youth, while I was born but yesterday–as he too knows–nor am I like a cattle-lifter, a sturdy fellow. Believe my tale (for you claim to be my own father), that I did not drive his cows to my house–so may I prosper–nor crossed the threshold: this I say truly. I reverence Helios greatly and the other gods, and you I love and him I dread. You yourself know that I am not guilty: and I will swear a great oath upon it:–No! by these rich-decked porticoes of the gods. And some day I will punish him, strong as he is, for this pitiless inquisition; but now do you help the younger.”

Homeric Hymn 4, trans. H.G. Evelyn-White

Zeus laughed to see his child work so hard and speak with such cunning to maintain his plot and deny his guilt, but in the end the god’s authority prevailed, and when he ordered his youngest son to show them where the cows were hidden, Hermes bowed his head to his father’s request. Swiftly the two young sons traveled to the cavern where Hermes had hidden the cattle, and though the boy began to drive them out into the fields at once, Apollo’s eye was caught by the two hides drying on the rocks from two cows that were flayed by an infant. “For my part,” he told the boy in his awe, “I dread the strength that will be yours” (Homeric Hymn 4).

Hermes’ physique was already as strong as his will, evident when Apollo attempted to bind the child with willow twigs. To the frustration and astonishment of the bright god, they fell away onto the earth and began to grow, until they had instead bound all the cattle. As Apollo’s fury began to return, the youngest god withdrew his instrument and quickly eased his half-brother with the gentle plucking of his lyre, singing of the deathless gods and the dark earth, and how each of the immortals earned their portion. The song began with Mnemosyne (memory), mother of the Muses and inventor of language and storytelling, because, as a poet and musician, the son of Maia is among her followers. Enchanted by the harp, Apollo proposed a trade: the lyre for his staff, which he told the boy would bring him leadership and fortune among the gods, in addition to the magic it had upon herds.

their portion. The song began with Mnemosyne (memory), mother of the Muses and inventor of language and storytelling, because, as a poet and musician, the son of Maia is among her followers. Enchanted by the harp, Apollo proposed a trade: the lyre for his staff, which he told the boy would bring him leadership and fortune among the gods, in addition to the magic it had upon herds.

Hermes accepted the trade, with one condition: that Apollo teach him the art of divination, which only the son of Leto knew. Apollo made Hermes into an omen himself, but gravely told the boy that the secrets of sooth-saying are not in his right to reveal; but that under a ridge in Mount Parnassus dwell three bee-nymphs, Melissae known as the Thriae or Coryciae, who know and taught to Apollo the art of geomancy and ornithomancy (divination by birds of omen). These maidens became Hermes’ teachers, as well, and Zeus placed both of their divinatory arts are his domain, in addition to naming Hermes herald of the gods, and Hades’ only messenger.

References

Hermes by Aaron J. Atsma

Stories of Hermes by Aaron J. Atsma

Thriae by Aaron J. Atsma

Wrath of Hermes by Aaron J. Atsma

Homeric Hymns, translated by H.G. Evelyn-White

Devotional Poems & Hymns to Hermes by Dver and Sannion

Metamorphoses by Ovid, translated by A.D. Melville

Bibliotheca by Pseudo-Apollodorus, translated by K. Aldrich

Great story of hermes and apollo. 🙂

Great story